Healing beyond borders: A Shanghai doctor's mission in Morocco

Doctor Zhang Baigen was the leader of China's first medical aid team to Morocco. The following narrative is about Zhang's story of healing patients in the African country.

In 1963, I graduated and became a vascular surgeon, aiming to be a good doctor. Then, in 1975, at the age of 34, I received a mission from my country and my hospital: to serve as the leader of Shanghai's first medical aid team to Morocco.

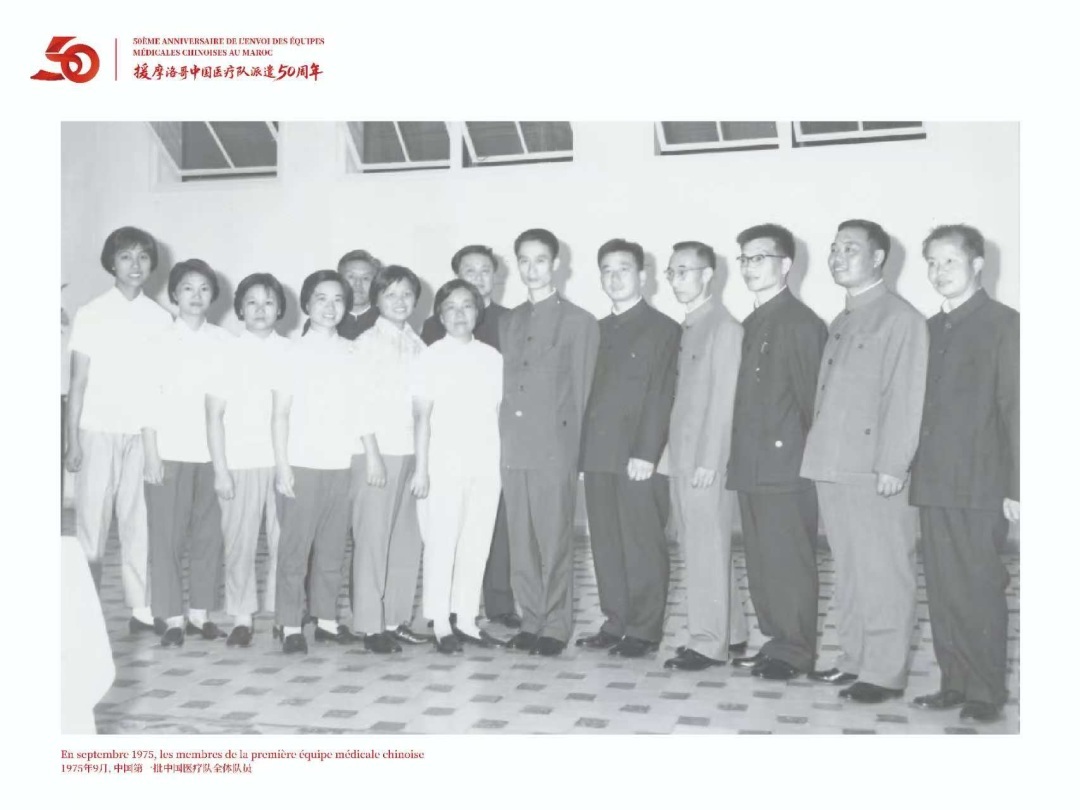

Our team of 12 was young. We came from Shanghai's top hospitals – Renji, Ruijin, Xinhua – and included a mix of Western medicine practitioners, acupuncturists, and other specialists.

After a brief period of diplomatic and language training and a long flight, we landed in a world completely unknown to us. Stepping off the plane, the unfamiliar scents and sights filled me with both trepidation and resolve.

Our first stop was the Chinese embassy in Rabat, the capital of Morocco. We found out we were the first Chinese medical team to be stationed in Morocco's local communities.

From there, we journeyed to our post at the Hassan II Hospital in Settat. Almost immediately, we were thrust into a relentless rhythm of work: daytime clinics, nighttime emergencies.

With limited resources, whether it was a minor ailment, a major surgery, or even nursing duties, doctors from Shanghai were on the front line. We were exhausted, running on sheer willpower.

Thankfully, our skill and dedication saw us through. We earned the trust and praise of the local government and hospital, even receiving the honor of being invited to the homes of the mayor and the governor.

Word of the Shanghai doctors quickly spread. Patients came from surrounding areas, and even scions of wealthy Moroccan families came to study medical skills. We learned local customs and diets, which facilitated our treatments.

I remember a severely malnourished child with an intestinal fistula. We realized the local diet was mostly dry bread with sweet tea, with limited meat and vegetables. I admitted him to the hospital. A nurse asked why I hadn't scheduled surgery. I explained that in the hospital, he would eat better than at home. We needed to improve his nutrition first. The boy eventually had a successful operation and went home healed.

As patient numbers grew, our small team faced an expanding range of diseases. I often wore multiple hats: general surgeon, orthopedic consultant, and even assistant in gynecological operations.

Compared to the medical whirlwind, our daily life was monotonous and harsh. Emergencies could consume any spare moment. The facilities of Hassan II Hospital were basic. Sweltering summers meant no electric fans, only ice blocks and hand-held fans for relief. The local government gifted us a ping-pong table and a television, rare sparks of leisure in our routine.

In this repetitive, demanding environment, one thing brought excitement: writing letters home. Fifty years ago, with no communication tools in our residence, we relied on the embassy to send our weekly letters back to China. Every page was filled with dense, small script, carrying our deepest longing for home.

People have asked me what sustained us through those tough conditions. It was the mission embodied in our white coats – a mission entrusted by our country and our patients.

One pair of eyes I can never forget. They belonged to an Arab woman from the countryside.

After giving birth, she experienced a retained placenta. She had wrapped the umbilical cord around her thigh, dragged herself onto a cart, and come looking for the Chinese doctors. We didn't share a language. But in her eyes – wide with pain, fear, and a desperate hope – I saw my purpose. That look was the very reason I had crossed mountains and oceans. We treated her carefully, and she recovered and was discharged.

Looking back on those countless days and nights in Morocco, even after 50 years, some memories may have softened at the edges. But those eyes, those expectant eyes, remain clear in my mind. Those two years turned my black hair grey, but every step was worth taking.

My hope for young doctors today is this: step out from the daily routine of the consultation room. Go to where the need is difficult. Go and look into those expectant eyes. Then, clad in your white coat, with dedication in your heart, embrace your original dream and shoulder the heavy, precious responsibility of healing.

Source: Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health