The art of Chinese calligraphy

Chinese 书法 (shū fǎ), or calligraphy, is the ancient art of Chinese handwriting. No publication on Chinese culture could ever omit mention of Chinese characters and calligraphy. For foreigners, 汉字 (hàn zì, Chinese characters) can be challenging, and calligraphy is even more difficult.

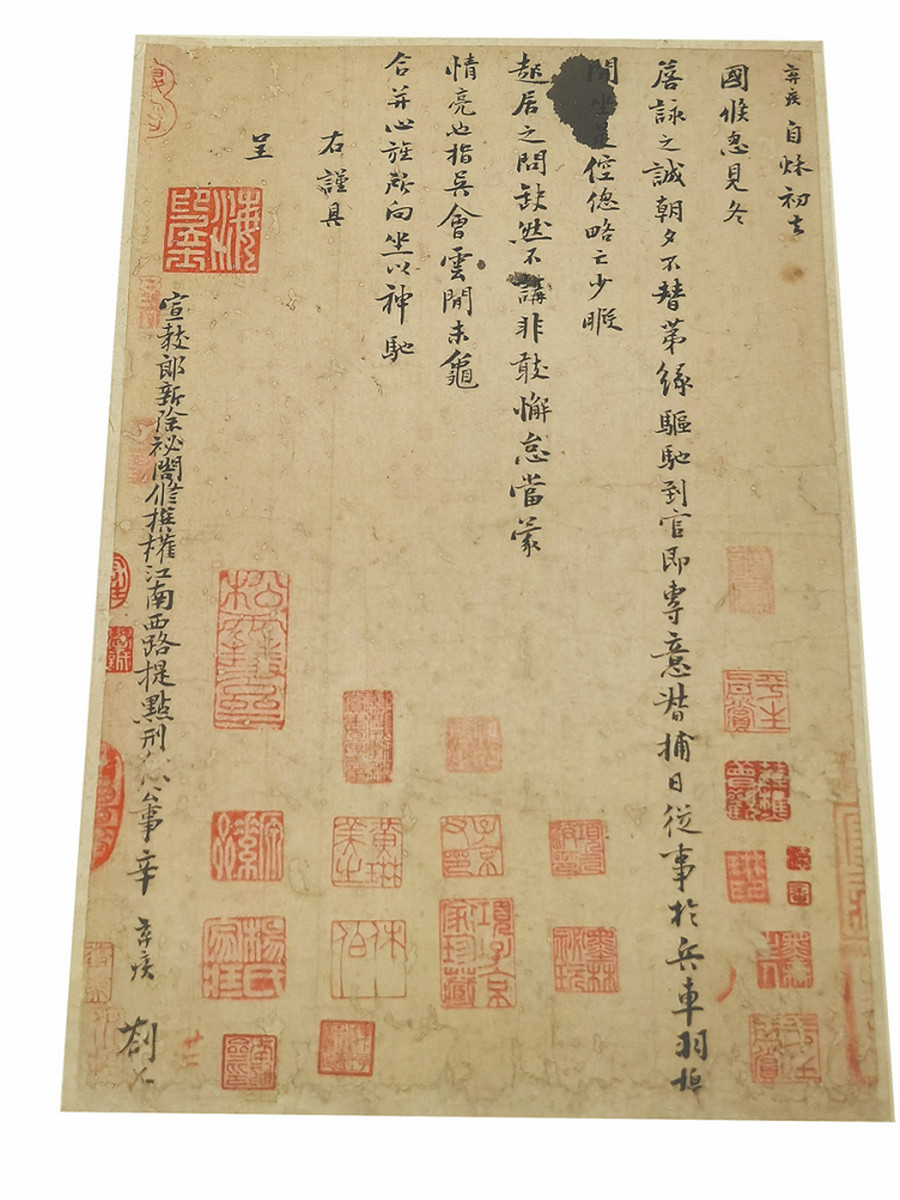

In Western traditions, calligraphy generally refers to writing with a quill pen (羽毛笔, yǔ máo bǐ), but it carries a different connotation in Chinese. 书 (shū) means 写字 (xiě zì, writing), and the original complex form of 书 refers to holding a brush with which to write on rice paper (宣纸, xuān zhǐ). In 书法, the character 法 (fǎ) signifies rules and laws. In other words, Chinese calligraphy means writing in a certain way and following specific rules.

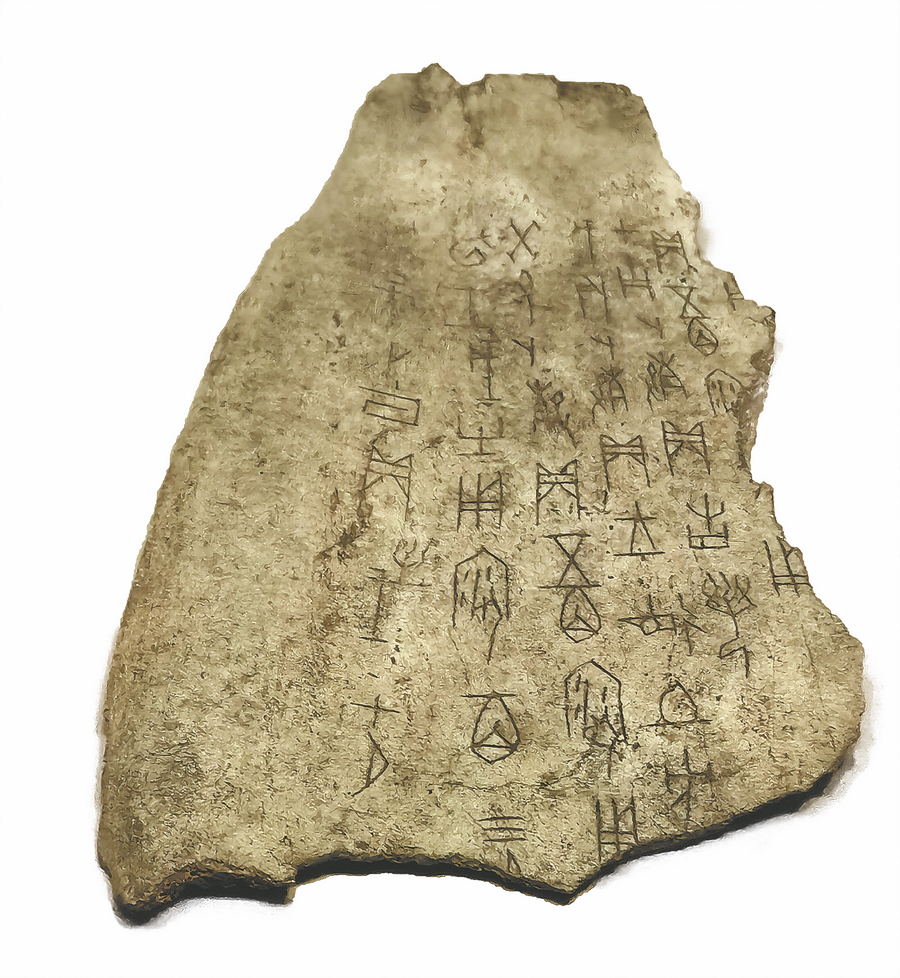

China's earliest written records are inscriptions on animal bones and tortoise shells (刻在龟甲或兽骨之上的文字, kè zài guī jiǎ huò shòu gǔ zhī shàng de wén zì), discovered from the 14th to 11th century BC. They are closely related to 占卜 (zhān bǔ, divination). In ancient times the Chinese used tortoise shells or cow shoulder blades to make predictions by heating them over a fire. A 巫师 (wū shī, shaman), would interpret the resultant cracks in the bones as foretelling future events. At that time, writing was regarded as sacred — solely for communication with the gods and as speaking for them, similar to the hieroglyphics (象形文字, xiàng xíng wén zì) of ancient Egypt (古埃及, gǔ āi jí).

For a period in ancient China, only 士 (shì, scholars and officials) could write. Ordinary people were generally illiterate (文盲, wén máng). The ability to write thus implied authority. The word 士 is still used, particularly in higher education, as seen in terms like 学士 (xué shì) for a bachelor's degree, 硕士 (shuò shì) for a master's degree, and 博士 (bó shì) for a doctorate.

In China, families of intellectuals or those with intellectual forebears are called 书香门第 (shū xiāng mén dì). 书香 (shū xiāng) has origins in relation to the practice of placing the herb Cymbopogon distans between book pages to repel pests. The faint scent permeating the pages made books fragrant. Intellectuals in China have also been called 文人雅士 (wén rén yǎ shì, literati or men of letters with refined taste). As their main tasks are reading and learning, they are also called 读书人 (dú shū rén, avid readers), or 学者 (xué zhě, scholars).

文房四宝 (wén fáng sì bǎo), the Four Treasures of Study, refer to the four writing tools: 笔 (bǐ, writing brush), 墨 (mò, inkstick), 纸 (zhǐ, rice paper), and 砚 (yàn, inkslab). 笔 is a pictographic character with 竹 (zhú, bamboo) at the top, signifying the material from which the brush is made, and 毛 (máo, the animal hair or fur) below it, representing the brush head. The characters 纸 and 砚 also reflect the materials they are made of — 丝 (sī, silk) on the left of the character 纸, and 石 (shí, stone) on the left of the character 砚.

Chinese forefathers held reading and writing in high esteem, a sentiment echoed in several traditional sayings. These include 读书破万卷, 下笔如有神 (dú shū pò wàn juàn, xià bǐ rú yǒu shén — One who has read ten thousand books, will write articles as if with help from the gods); 腹有诗书气自华 (fù yǒu shī shū qì zì huá — reading makes a person graceful); and 读书千遍其义自见 (dú shū qiān biàn qí yì zì xiàn — the meaning of a book begins to reveal itself after reading it a thousand times). Even now, Chinese students and scholars take heed of these sayings, believing they provide both methods and inspiration for study.

Using a writing brush (毛笔, máo bǐ) differs from using a ballpen (圆珠笔, yuán zhū bǐ) or typing in that it requires a greater connection between the mind and the body. It calls for profound interplay between the calligrapher's heart and the world he presents on paper. Calligraphers regard their works as reshaping the cosmic world. To achieve a state of harmony between nature and human beings, they sketch the rudiments in their mind's eye before they 挥毫泼墨 (huī háo pō mò, wield their brushes to write in ink).

Every calligrapher has his or her own way of 运笔 (yùn bǐ, writing each stroke of a Chinese character). In the long practice of this art form, they may have developed their own distinctive 笔势 (bǐ shì, writing styles), which evoke different feelings for their works.

In China, there are thousands of ways to describe calligraphic works, such as 龙飞凤舞 (lóng fēi fèng wǔ, lively and vigorous); 圆润流畅 (yuán rùn liú chàng, smooth and fluent); and 清和淡雅 (qīng hé dàn yǎ, gentle and graceful). There is no lack of Chinese expressions complimenting such works. Chinese calligraphy is a revered art form and makes a treasured gift.

Source: China Today

For any concerns regarding copyright infringement, please reach out to us at intlservices@shanghai.gov.cn.